Recently I saw a video titled “TDD for those who don’t need it”. It was plain and obvious. But then it struck me, as I realized that there are more places where, I believe, teams work based on some plan and later, at some point … they don’t. In this post I will show you an example of an idea that is destined to become a production-ready feature. What the work looks like at the beginning, and what happens to it later.

Aha, I have a great idea!

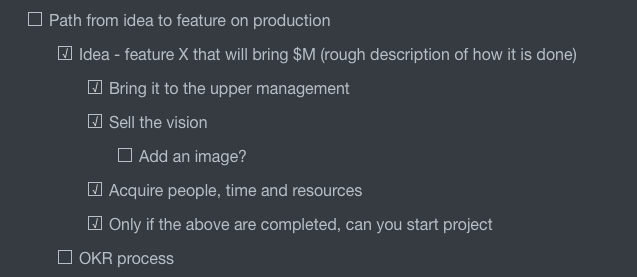

Cool. So, what do you do about it? Most likely, you will bring it to the upper management in your company to get approval (that’s your initial goal). You need to sell the vision (“This awesome feature will bring us lots of $, you’ll see!”). You’ll need to present the requirements and costs—that means people, time, and resources. And if you succeed, when those requirements mentioned here are fulfilled, only then can you start working on this project.

OKR FTW!

What is it? Objectives and key results (OKR) is a framework for defining and tracking objectives and their outcomes. You can find out more here. Let’s assume your company works based on that framework as well. So, again, you need to first come up with a list of checks that you will be wanting to fulfill to say—our work is done. All of your future activities will revolve around them. All of your future actions will be checked against them. What role do the OKRs play here? They are there as a guard, preventing you from falling into a trap where you’d do something new rather the important thing.

All right. OKRs are done. You can start …

Planning with the team

tl;dr—you create epic stories, you cut them to smaller ones, you prioritize. For each story, you discover what the dependencies are. Again, you create sets of checks against which your work will be done. You will do no more, you will do no less (yes, you will want to go the agile way and adapt as you deliver stuff, but you catch the drift). And only if all of them are completed—your big project is finished.

Next thing is …

You grab a ticket

You take a ticket, and only if the ones this one depends on are done. You will only mark it as done when your code is merged to a master branch (and tested on production; however the process looks like in your case). Does it sound familiar? Does it look, again, like a list of checks, defined upfront, before a ticket can be closed?

Finally …

Coding

At last, you can do some magic (or witchcraft with technology). But all of a sudden things begin to take a different path. You write the code first, and add (if at all) some tests later.

Why would you do it in this order now, when with every step on the way, up until now, the very first thing you did was preparing checks related to the work you will do later? You didn’t start working on the code, before taking a ticket—so that you knew what to do. You did not pick the ticket, before doing some planning and prioritizing—so that you knew what to do first. You did not start the planning before OKRs were defined. And finally, you did not work on the OKRs, before there was a green light for the idea itself. I will ask again: why would you start working on a piece of code before knowing what this code was supposed to be doing?

Suggested approach

I am not going to tell you what are the benefits of TDD (like confidence, speed, fewer errors, better design, less code, etc.—you can find all of that information for instance here). I will tell you why you should try it and how.

Let’s take a simple feature as an example. Here are some requirements for one of the tickets:

As a user when I click the submit button:

- I want to send the form data

- display the spinner

- when the response comes back the spinner disappears

- and confirmation box with some message is presented

(for the time being, no error handling is needed, we want to move in small steps and improve as we go)

Having that, how about a test suite, like this one:

Test suite example in Mocha JS

context('when the button is clicked', () => {

it('should send a request with data from the form', () => {});

it('should show the spinner', () => {});

});

context('when the response is back', () => {

it('should remove the spinner', () => {});

it('should display confirmation box with a message', () => {});

});

// no implementations, for the sake of example

Did you notice a 1:1 resemblance to the ticket requirements?

Most of the times, when I spoke with some engineers about reasons for not using TDD, I heard that it was hard or uncomfortable, as they were not sure where to begin. With this approach, you can easily start your journey using test first / TDD technique. The only thing you need to do is follow the requirements in the ticket … which you will have to, eventually.

Having this initial set of tests, it will also be easier and more comfortable for you to add new tests for new requirements, that will come with the following tickets.

Conclusions

The thing you will need to remember is that all the way from the birth of the idea, to the point when you strike first keys to produce the initial code, will require you to set some acceptance checks. Whether it is a high-level concept or a subtask with very clearly defined requirements. Thanks to that you will know what to do. You will know where to start. You will have a clear list of tasks that will tell you if you are done or not. In terms of tests—any red test !== done. I encourage you to try this approach, it is easier than you think.

PS: even this very post had had a list of checks for me, to verify if I had not forgotten something before publishing. And I wrote those checks up front as well, before a single word for the article was written.

Excerpt from the whole checklist for this blogpost

Main photo by Matthew Henry on Unsplash

Idea image by TeroVesalainen from Pixabay

Coding image by StockSnap from Pixabay