Visual regression testing has recently started gaining popularity- and for good reason. At its most basic, it’s a series of tests that run through your site, take screenshots of various components, compare those screenshots against a baseline, and alert you when things change.

(Css-tricks; Visual Regression Testing with PhantomCSS; November 17,2015)

The reason behind the change

HolidayCheck, like any other company, needs to run its business not worrying that some changes might break its product. One of the ways of maintaining that peace of mind is to ensure that visually everything is A-OK.

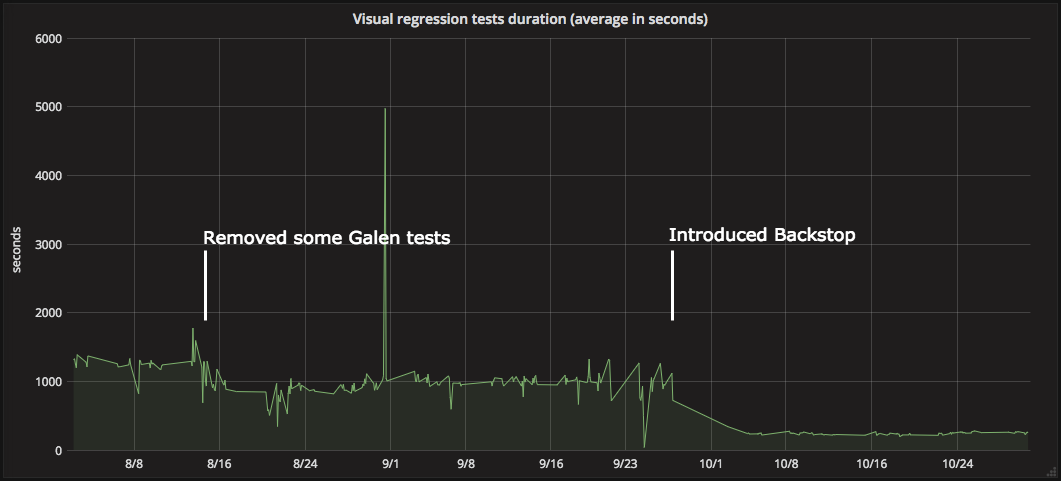

How did we do that? Our project used Galen as a test runner. Tests were executed on external virtual machines using the WebDriver protocol. From the very beginning, we felt that that setup was slow and problematic. Every test suite was executed on a new virtual machine, which had to be booted up. Furthermore, our testing environment wasn’t publicly accessible, so we had to use tunneling. We were able to find some workarounds to specific problems (like moving our test server closer to the external provider’s machine) but time and lack of reliability were an issue. Taking all that into consideration plus the number of tests that we have had, our mean time for running visual regression tests was 20 minutes.

There is one more reason why this value was even more problematic for us. The way we work is that we require our feature branches to be on top of the master branch. When somebody merged something to the master branch, you had to rebase. That meant yet another 20 min. What if this time the tests have failed (as they have, quite often)? You would have to rerun them. What if something was merged again? You’d have to rebase, yet again, and pray, that the random fail wouldn’t happen. Some features took hours to get to production.

Enough was enough.

Call for action

The first thing we did was removing some of the tests—the ones that were not essential for the business to run. We managed to go down from 20 to 16 minutes. But that was not enough. And we did not remove anything regarding random failures. What we gained, though, was a list of tests that really mattered. And those were the ones we decided to migrate.

The search for a replacement for Galen was rather short. We googled for some solutions, but we also checked our own backyard and found out that another team was using BackstopJS for their own project. The decision was easy: let’s not use yet another tool, creating yet another knowledge silo. Let’s use something that is known and, more or less, proven to be working.

Migration plan

First, make it work

First of all, we needed some proof of concept for our solution. That meant running one test, for a single URL, no interactions, just a screenshot of the entire page taken. That meant we needed some configuration, a single test suite and some code that wrapped all of that and executed the test. If you were to look at the file structure (responsible for running this test), it was far from perfect. But that was OK. We knew that things would change on the way.

Let’s take a step back for a brief moment. How many times did you think about how to structure your app or how to name that class or, even, what this particular single variable should be called? I guess many. And was that an easy thing? Should you know how to do that from the very beginning? The answer is a simple no. It is hard and time-consuming. You won’t know those things until you use them, or use them more often. Not until you change something. Then you refactor (the file structure, the class, the variable name) and adjust on the way. Make it simple at the beginning, but most of all, make it work.

Getting back to our tests. Having that done, next step was to make it easy to use. For that, we’d created a few makefile recipes so that everyone could just go to the terminal, enter a single command, and wait for the results.

Scale the migration vs. migrate less

It turned out, very quickly, that the whole migration was going to be a time consuming task. We then raised the question: do we need all of those tests? More tests equals more time to migrate them. Such a number would also mean it will take longer to run them. How much longer? We couldn’t tell, as we only had one.

We thought: if it will be trivial to migrate a test, perhaps we could migrate them all. After all, they were there for a reason. We could then see how long it takes to run all of them.

In order to do that, we needed to simplify the way we wrote the tests.

Kent Beck once said:

for each desired change, make the change easy (warning: this may be hard), then make the easy change

— Kent Beck (@KentBeck) September 25, 2012

And that is what we did: we made it easy to write the tests so that it was easy to migrate them (make the change).

That task consisted of three steps:

-

Simplifying test structure. Eventually, we came to the point where taking a screenshot of a page under a given URL looked like so:

Test suite with one test case

// tests suite module.exports = [ // single test { path: '/to-some-page', label: 'label-for-that-page' } ]; -

Preparing basic, very abstract interactions (click, input text, scroll, wait for element, etc.). Let’s say you wanted to input some text and submit the form. Here is what you had to do:

Interactions usage example

const { CLICK, INPUT_TEXT } = require('./interactions'); module.exports = [ { path: '/to-some-page-with-a-form', label: 'label-for-that-page', interactions: [ { type: INPUT_TEXT, selector: '.some-form-field', text: 'Hello, world!' }, { type: CLICK, selector: '.submit-button' } ] } ]; -

And finally, writing the docs on how to migrate the tests, so that others could understand and follow.

When all of the above were done, we split the task between a few of the guys in the team and migrated all of the tests.

Did it go well? Of course not! :)

Problems

Navigation on mobile devices

One of the tests was about clicking on a menu item to drop it down to reveal a submenu. The trick was that this element behaved differently on a phone (clicking was not resulting in redirection). The Galen test had it done in a simple “click a selector”-way. It took us a while to find out that there was a hack included that had overridden the touch event:

Script disabling redirection for mobile devices

window.document.documentElement.ontouchend = {}

As Puppeteer allows us to easily control the browser (Chrome in headless mode), we were able to order it: emulate phone. And we did that. And it worked. But other tests failed. After trying some solutions, we had to use the aforementioned hack eventually. Luckily, thanks to how we prepared all of the interaction, this script was hidden from the outside world in a form of a DISLABLE_REDIRECT_ON_MOBILE interaction. At least it was easy to use.

Loading lazy loaded images

The problem: have them triggered (by scrolling the page) and loaded (image is completely loaded) and visible (browser finishes rendering it) before the screenshot is taken.

And oh boy, did we struggle with that.

Again, a little side note: the problems with solutions defined below did not occur until we shipped the code to our pipeline and ran tests multiple times. Locally, everything was fine at each step and for every test. Hence the struggle.

Approach no. 1 — add the timeout

Lazy way: let’s just wait some arbitrary amount of time and hope for the best. Sadly, the tests were not conclusive. The variable in the process was the CPU that ran all of the things: starting with firing up the browser to running the tests, making the screenshots and comparing them with the reference files. The more test jobs we run in the parallel, the more the CPU was consumed. The more the CPU was consumed, the longer it took to have the images to be fully loaded. No. That was not the way to go.

Approach no. 2 — let’s go fancy, MutationObserver to the rescue!

tl;dr: MutationObserver API allows you to observe the changes being done to DOM and react accordingly.

Simply put: listen to the parent of the lazy loaded stuff, once the DOM structure changes (within that parent), call some callback. It helped us in the sense that the tests were more reliable. Still, the main problem with this approach was that one parent could have had more than one sibling that was lazy loaded. We searched for all of the images, counted them and in the everlasting loop counted backward. Once all were loaded, the loop was terminated. You can imagine how problematic that could be. We still had to wait for the images to be rendered. And again, the CPU variable came to play. No, too much hassle.

Approach no. 3 — what if I promised you …

Who doesn’t love Promises, right? The solution assumed attaching event listeners (for the load event) to the img elements and waiting for all of them to trigger, like so:

Script waiting for all of the images to load

const waitForImagesToLoad = async page => {

await page.evaluate(`(async () => {

const allImages = document.querySelectorAll('img');

const promisesForLoadingImages = Array.from(allImages).map(image => {

if (image.complete) {

return Promise.resolve();

}

return new Promise(resolve => image.addEventListener('load', resolve));

});

await Promise.all(promisesForLoadingImages);

})()`);

};

It proved to be the least flaky out of the three.

Again, a sidenote: you have probably spotted the `` wrapping the callback. We wanted to run Backstop programmatically, not as a CLI tool. When run programmatically by babel-node (which we have to do, because our server code requires transpilation), async is rewritten and thus not compatible with Puppeteer. You can find more info here.

Approach no. 3.1—add the timeout, yet again

As it turned out, the CPU usage was still an issue, so we had to add this timeout. Luckily, not that much this time (100ms).

Final solution

Eventually, this was our solution for lazy loaded images:

- Scroll down to the bottom of the page; do it in steps (viewport height), with a small delay, 50ms, between the scrolls, so that the CPU has a time frame to alter the DOM if necessary.

- Scroll back up, to the top of the page — by that time all of the lazy loaded elements were triggered and DOM was altered.

- Attach event listeners (

loadevent) to theimgelements. - Wait for all of the events to resolve.

- Wait a bit more (the 100ms time).

Done.

Animated elements

At one point we’d spotted another randomness. Some elements were higher in one tests and lower in others. Or their positions differed. And by a random number of pixels.

It turned out that we had some CSS animations taking place. And again, depending on the CPU usage, animations were finished or not.

We tried delays, as our first approach, but that did not work. We then used a trick that solved current and future problems with animations: set the animations time to 0. Here’s how we did that:

A little trick used to disable CSS animations for all elements

await page.evaluate(() => {

const instantTransitionCssRule = '* { transition: all 0s !important }';

const styleElement = document.createElement('style');

document.head.appendChild(styleElement);

styleElement.sheet.insertRule(instantTransitionCssRule);

});

The above script is executed for each test, just before any interactions for that test are executed. Another randomly occurring problem was solved.

Threshold problem

Usually, visual regression tests have a threshold: a number of pixels which can differ, and the test will still pass. Sometimes intentional change isn’t detected (for example, changing size of the X mark in a close button). If a screenshot is taken for the whole big page, like 5-page-long viewports big, that difference might not be caught. We know about that, and we accept it. We understand that such a change (and a false-positive) is not crucial to the business.

Switch

For a while, we ran both (Galen and Backstop based) visual regression tests in parallel. After having the Backstop one stabilized, we turned the other one off.

Git repository and storing reference files

One of the things we perceive as crucial is the possibility to clone the repo of our application and with just a few commands run it or execute the tests. It should be self-contained.

What about storing reference files inside the repository, then? Should we keep them there? We decided not to, and to put them on the server, where all of the tests are executed. Why? For two key reasons.

1. Differences in rendering

Despite the fact that all of the tests are run in the same browser everywhere (headless Chrome), it is not guaranteed that the rendering will look 100% the same on various OSs. E.g. I am using macOS, my colleague is using some Linux distro. I bet there will be differences. If he were to submit new reference files, tests on my end would fail. So could the ones executed on the pipeline server (yet another OS).

We could use Docker to ensure we have the very same environment everywhere, but that just adds too much complexity ‘only’ for running visual regression tests.

Sidenote: we still can run the tests locally. For that it is required to:

- Make the reference files from

masterbranch. - Apply whatever changes in the code.

- Run the test(s), and the images created will be checked against the ones created on the same OS.

2. Large amount of files

Right now, our reference files weigh ~85MB. Let’s say something gets changed in the header of the application. Most of the images would have to be refreshed and, say, ~60MB of new ones would be created. What would that mean? Downloading that ~60MB of data on next git pull, or a whopping ~145MB of data on git clone. What if more changes are applied, or reverted? More and more MBs to download. That would be just too much.

There are ways of bypassing this. One of the solutions is to use LFS. Yet, using that extension doesn’t fix the no. 1 problem (rendering).

Therefore we decided to keep the files on the pipeline server, where the whole environment is constant.

Final words, learnings, possible improvements

Occasionally we had, and still have, some tests failing from time to time (lazy loaded images, very rarely), but we are satisfied now. The most important thing is that we can ship more often. We went down from ~20min to ~4 with our visual regression tests!

Visual regression tests duration (average in seconds)

As we have previously tested our application against various devices, we came to the conclusion that perhaps we don’t need to be so precise. Maybe it is OK to have it tested against the most popular browser out there (where most of the modern browsers behave almost identically) and on one device. If something is moved 3 pixels to the right in another browser/device - then so be it. The most important thing is that it is there, and that is what those tests are all about.

The most important thing is that the time (20 minutes down to 4) and the money saved (from the time to release and dropping of virtual machines from external partner) can now be used elsewhere, e.g. to provide more features to our customers.

There are a couple of things that can still be improved. One of them is not taking the screenshot of the entire page when you want to test some state change of one of the elements on the page. You can take a screenshot of that one element only, thus making the comparison slightly faster. We could also remove some tests. But that is not the bottleneck right now.

Photo by Barth Bailey on Unsplash.